My friends in Detroit are obsessed with list-making. They’ve all been on the hunt for personalized license plates of late, exclaiming “BB Benz” or “VIBER8TR” at the top of their lungs at unpredictable intervals while driving. I notice one on my way to Judith Supine’s show at Red Bull House of Art. It says “THIRSTY,” which is so funny to me that I snort, laughing. I make a mental note to share it with my friends when I see them tonight, so they can add it to their catalogue.

Judith is showing with Lucien Shapiro and Julie Schenkelberg in a group exhibition capping their residency at the venue. Andrew and I park beside a giant tank of liquid nitrogen in Eastern Market. Andrew says the nitrogen is likely for flash freezing, which makes sense as there appears to be a factory of some sort at the end of the street. He also assures me that it isn’t flammable, which quells the swell of anxiety a large tank of liquid can command in me – especially before entering a confined space with a large crowd.

We wind through people. Lines of them working on getting inside, and great queues of them getting drinks and going downstairs to the gallery space. So many people. Every activity comes with a lineup. Downstairs finally, I run into some friends in front of Julie Schenkelberg’s work. They point out a dead deer nestled into a corner of a sculpture.

“Is it taxidermy?” I ask. “No. It came frozen.” “Oh.”

I hear Andrew ask the same question.

“Is that taxidermy?” “No, it came frozen.”’ “Oh.”

I wave at another friend directly across from me, on the other side of the dead deer. It is a bit awkward to wave at a friend over a dead deer. I feel sweaty.

We pass through a room full of crystal scepters and other protective items made from rebar and old bottle caps. We are in Lucien Shapiro’s realm. It’s sharp witchery. I’m glad that I wore my most powerful Hamsa, as the energy in the room pulses with a fierce intermixing of time-heavy rusted steel and the ingathering of so many crystals that I feel close to levitation. I seem to exit this portion of the room unharmed, but it’s tough. There may be after-effects.

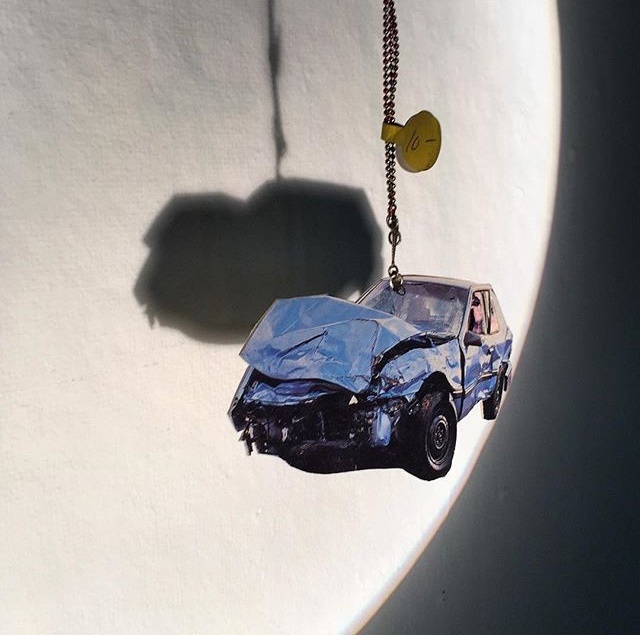

On the far wall, I find Judith’s clocks and am comforted by their fragile whimsy. The clocks are tiny, but explosive. Supine authors a powerful myth out of three simple images strung together by chain. They tunnel my vision amid the overwhelming crowd. They tell me close, insular stories that stave away my anxiety. A Scorpio with a blade. A car with its front end crashed in. A smoking cowboy with a male torso growing out of his hat. The head of a man in mirrored sunglasses. Each image is meticulously cut out and connected with old chain in a variety of golds and silvers. The chain that suspends the crashed car still has its barbell price tag on it: ten dollars. It too, becomes part of the fragments that make up this story. I find the crashed car more vulnerable under the faded tag, as if the driver of the car wound up in the hospital with a crumpled ten spot lodged in his pants pocket. His last ten dollars, even. His vanity plate would say: PENNYLE55.

MJB: I am thinking about your clocks right now. They are very heavily edited – a translation of an imagined universe into something tangible. They are their own worlds. I am guessing there were thousands of images that you sorted through to make those. But you wound up using them sparsely.

JS: Yes. Sparsely.

Tell me how this aspect of your practice relates to writing.

When I think of writing, the part that I think relates to my process or practice is learning to edit. It has been important to try and mimic the way a writer would edit and heavily edit. No one would write a book and include everything. Artists barely edit themselves. This work is about refining completely.

The clocks are micro narratives, almost.

Yes. I kind of think of them as paragraphs. There are portions of necklaces and chain separating each. I think of the length and distance of the chain according to how long I want a pause to be.

Are they wordless, these stories?

They are supposed to have some kind of feeling to them. I try to make them a bit uncomfortable.

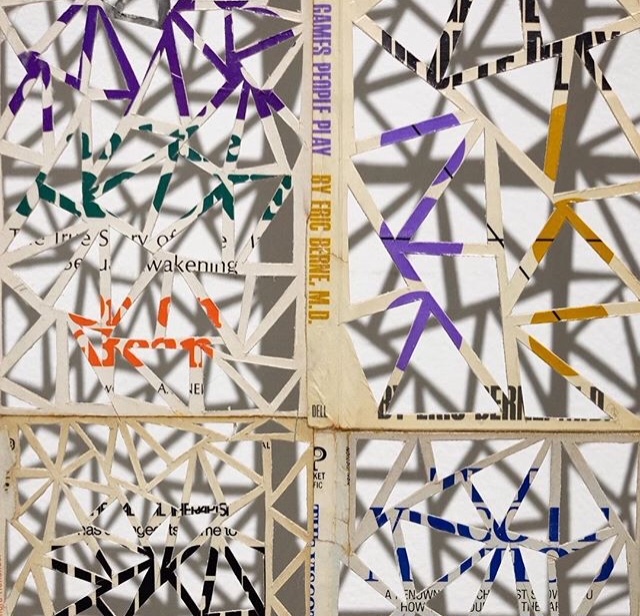

But there are words in some of the sculptures, no? Where do the words come from?

Those are cut from book covers. I thought of making some sculptures that are just words. Little poems. I don’t know if that would be too heavy-handed, but I like the aesthetic of those cut-out words. That super high gloss and the weird fonts. One of them I like is: “too, too solid flesh.”

Tell me how this differs than your other collage work?

For me it is a different way of making collage – a move away from making one solid image, where you stick a bunch of shit together to make something new. I wanted to actually start to write with collage and not affect each individual image at all. Just let each image stand alone, but have it connected in a looser way, and let people make their own associations.

Can you run me through one of these stories that you have put together?

Um, no. I don’t think that I can.

***

Judith is running late, caught up at a taco truck in the Southwest. We’ve been there together before, and so I get how eating at El Taco Veloz is sexier than meeting me for an interview. I settle in with a muddy coffee and wait, staring out the giant window at the large black-and-white mural along the building, home to the formidable letterpress studio, Salt and Cedar, until recently. The painting indicates, with a long and definitive arrow, a true meridian. I’m more than content to observe from here, until the tacos are done, and Judith is shuttled across town, intersecting the ley-lines of the city. Brad is driving, and I am not worried. Brad knows what’s up with Detroit.

My particular Detroit is all about unearthing books. The afternoons of my youth were spent perusing John King Books, its massive powder-blue warehouse, a beacon nestled beside the freeway: a giant dust, cases of ephemera and row after row of bookshelves. I remember Judith mentioning that a lot of the materials for the works he made in Detroit came from John King. I wonder if he met John in his overalls. I wonder if the sparse Glenn Gould poster hanging in the stairwell between the second and third floors felt as buoyant to him as it did to me, or if the honeycomb of volumes piled at the entrance got his heart beating as much as it did mine.

In my twenties, I had a love affair with a longtime bookbinder at John King, who sometimes did an obscene amount of acid and stayed home to read philosophy books. He kept an assortment of pristine white gloves in his satchel at all times. He was a keeper of worlds, patiently working to save paper from some sort of demise. Judith’s latest work has a similar resonance. I can imagine him patiently razoring out psychically-attuned images and phrases, spending hours deciphering and distilling them into delicate, emotional stories.

Did you get to meet John King?

I did. I wonder what John King would think about the show. I know that everyone was a little perplexed as to why I was buying a hundred red books.

Why a hundred red books?

Right now I am into making these pieces that are like quilts. I take one hundred and eight books that somehow relate through subject, color, or feel, and make them into quilts. That came to me by looking at the Gee’s Bend quilts made in Georgia.

What is your obsession with paperbacks? Is there a particular type of book cover that you collect?

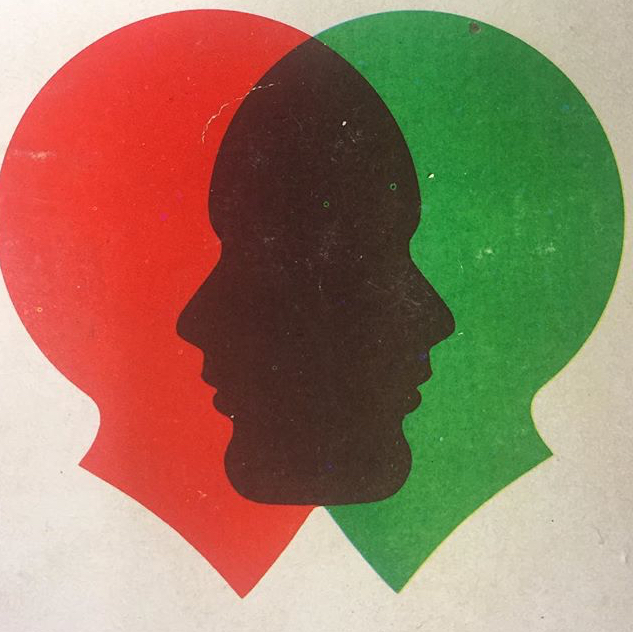

I collect books. For me, the main thing is that I almost get high off of amassing book collections. If I know there are twenty-six books in a psychology series and I only have some, I am always looking for the rest. There are some books that I like because of the oddity of them and some that are just beautiful. I like the 1960s or maybe more 1970s psychology books. They have graphics of heads within heads within heads, with reds and oranges or reds and greens. I am attracted to those. My brother and I have been into book covers since we were kids. We used to have collection of Elmore-Leonard-type of books with weird covers that possess a certain feel. I used to be super into going to the video store when I was a kid and looking at the old VHS covers – not even watching the movie – and I would kind of fantasize based on the one image. I do the same thing with book covers now. My attraction to certain covers relates to this memory of the video store.

So book covers kind of create worlds for you to work from?

Yes. The covers all sort of start to relate to me. There is a nostalgia to them. There tends to be a kind of narrative I create in my head – a little fantasy, which is kind of like what I did when I was a kid … live in a pretend world.

In my younger years in Detroit, I wove amongst ceiling leaks and broken spines in the abandoned book shop across from Zoots on Second and Prentis, excavating first editions and odd ephemera from the damp old shop and poring over them in the Bronx bar afterwards. The poems of Phil Levine, or a book on the Surrealists kept me company as I tucked myself into the corner of the old dive bar for hours. I went to visit the Bronx a year ago, and was relieved to learn that the same bartender was still there, even as everything has gentrified beyond recognition around her. I think, too, of the rows of letterpress type and the orbits of poets that enlivened Salt and Cedar, where I read my own poems and also ate crickets for the first time. This city is a palimpsest of paper and ink and ideas that have shaped my worldview. It’s thicketed with narrative and artifact. Supine’s work captures something of this heterotopia for me: gorgeous and sad and lost, while at the same time existing uncomfortably with its retrieval. It is the too, too solid flesh of the city, with a soft underbelly of thrift-store chain and faded quilts with tufts of stuffing peeking through.

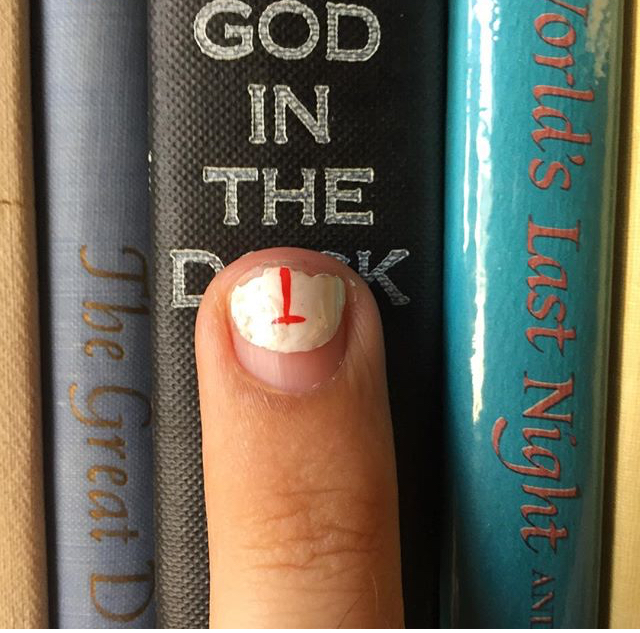

The first time I met him, I was riveted to his white nails. I had to ask him to hold his hands out so I could read the letters inked across them. “Easy Does It,” they said, in thin sharpie – one per nail. “Do you do nails yourself?” I ask. “No. I just feel good in the environment a nail salon offers. They are matriarchies. I like matriarchies.”

I want to know about your nail polish thing.

Um, I started the past summer my friend was dying in the hospital. He wanted me to do his nail polish for him. So I was like, yeah, I will come back and do your nail polish tomorrow. I went back the next day and he was non-responsive, so I just did my nails instead. I have been doing them ever since.

Why do you want to open a nail salon?

I like the atmosphere. I feel comfortable. I like it when women are in in charge. It’s the most sympathetic audience for me. They are spaces that are reflective of my actual values; my feel and view of the world. I want to make things that are beautiful and gentle. I want to make things that are tender, careful, and more pensive. The nail salons embody some of this.

***

The last time I spent time with Judith, we all met up here at Trinosophes: Judith, his brother, our friend Tyler, and me. We hung off of a corner of a communal table, fixing on a cruising tour of the four corners of Wayne County. We took Tyler’s ride straight up Gratiot, engulfed by its expansiveness – a tiny silver capsule full of skin and bones, breathing and looking. I imagine cars used to parade along this vast road inside of another kind of dream, full of trips to chromed donut shops and Sunday masses, or perhaps a trip to Dream Wings after a hand wash at William’s. Gratiot goes on forever.

Judith keeps his eye out for property. He wants to open a nail salon, he says. Tyler points out that here in the outreaches it may be hard to get actual customers. I don’t really think that matters, though. I could be wrong, but I sense that the nail salon exists in another, auric dimension of Gratiot, where the more pragmatic elements of the venture are irrelevant. Not that I doubt at all that Judith’s plan, It simply feels as though there are layers to this concept, nested within the past and potential that unfold as we drive. Judith selects a low-rise art deco building along the next tract of the road. It strikes me that he’s at work discerning the items in this visual landscape that suit his vision, just as he might cull book covers for his next collage work. He makes a list of potential names as we drive. Nail Bait. Nail Biters. Jesus’s Nails. You’ve Got Nail. They are the punctuation of our drive down the grand, endless avenue.

Thanks Melanie for the peek into Judith’s work and life. Makes me want to come back.