One of Tracey Emin ’s best known and most controversial works, My Bed, first made in 1998, and once in private hands, is now on long loan to Tate and on display at Tate Britain. To accompany its return to the gallery (it was first shown in the Turner Prize display), Emin has selected two of her favorite paintings by Francis Bacon, an artist she has long admired, as she tells Tate Etc.

Editor Simon Grant interviews Emin on her selection of Bacon paintings and the difference between having an affinity and a dialogue.

Why did you choose two works by Francis Bacon to show with My Bed?

Nicholas Serota and I were talking about how to present My Bed. Some people suggested showing it at Tate Modern, but I wanted it to have a very different context, not with my contemporaries, or in a ‘best of British’ kind of selection. I wanted to make a statement with it, so I said I’d like to show it with Bacon, because I thought there would be a really good dialogue between the intensity and anger in his work and the way the bed has this sense of collapse and seems completely forlorn. And there’s also this kind of debauchery and craziness going on between both artists, but done in a completely different way.

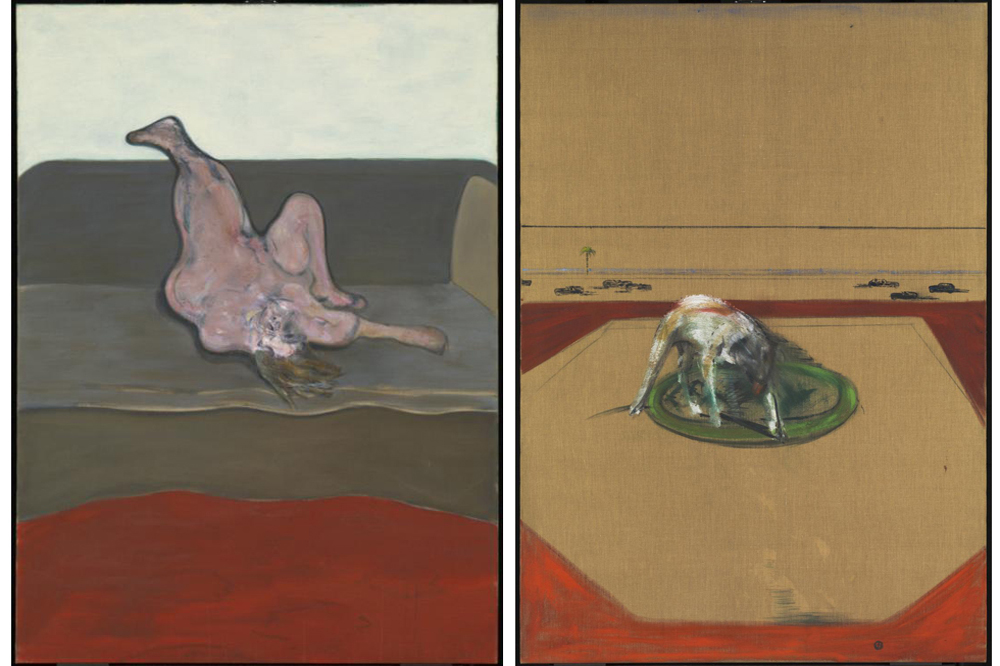

So from all the Bacon works at Tate, you chose 1952’s Study of a Dog and 1961’s Reclining Woman…

When I saw Study of a Dog I said yes immediately. It has an insaneness about it. The whole thing is completely strange; this dog is trapped within a hexagon-like shape and spinning around in its own space as if wanting to escape. The background looks like Los Angeles or somewhere non-British. It’s a fantastic painting – the technique is so minimal. How did he know when to stop working on it? With Reclining Woman, I never knew Bacon would look at a woman, let alone paint one. It’s not what you’d expect at all. So maybe it was a man who he thought looked like a woman? I like the waves of the bed, the way it resembles a river. I like the blood red color – it is so intense. It would have been too obvious for me to show one of his bed paintings. This isn’t obvious, because it has this landscape quality. With My Bed, its strength is getting the sense that someone has just got out of it. In the Bacon picture, if this figure were to get up, you’d actually see where she had been lying.

Is there something about the way that he focuses on the single figure that connects with a lot of your drawings?

Yes, but in a lot of his paintings, even if there’s one figure, it looks like two. They appear to be fighting or fucking, or there’s one coming out of another. I preferred Reclining Woman because it seemed to me to have much more of a connection with My Bed. We don’t need to see two figures fucking or fighting. With the bed, we can see the condoms, the stains on the sheets, and all the detritus of love and sex. We don’t need to see that again in a Bacon painting. What we need to see with the bed is that someone lonely walked away from it.

Is that sense of loneliness something you see in the Bacon pictures?

Definitely, especially Study of a Dog. It is something that as an artist you always feel at some time. You can’t be everyone’s best friend and be a good artist – you’d be kidding yourself. Jackson Pollock? Who would want to have dinner with him?

Did you ever meet Bacon?

No. I only ever saw him once – on South Kensington tube station. We passed on the escalator. We didn’t make eye contact.

Was he on your radar when you were a student?

Yes, because I am a figurative painter. But to me then he was always a bit weird and macho – the drunken boorish artist. But after Gregor Muir [now director of the ICA] showed me his series of Pope paintings I saw the fecundity in his work that I hadn’t previously seen. I always thought he was a good painter, but I didn’t get it until I saw it through different eyes.

Through a man’s eyes?

Definitely. Not through a homosexual man’s eyes, but he showed me what was going on. Before, I’d always seen the pictures as this robust single figure. In a strange way, I still do. There may be two figures, but it looks like something in turmoil; like someone’s soul fighting.

So you feel an affinity with him in that respect?

Well, yeah, my soul fights, but I don’t have an affinity with Bacon. I chose his work because there’s a dialogue. It’s not an argument, but there’s friction going on – there’s something happening between us.

Tracey Emin, My Bed, 1998. © Tracey Emin. Photo credit: Courtesy The Saatchi Gallery, London / Photograph by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

You’ve certainly chosen some interesting Bacons …

Maybe that’s because I’m a woman. There are lots of boy artists who really respond to his macho themes.

I always thought he seemed more vulnerable to the world than that.

No … well, maybe. It’s nice of you to say that. I think he came across as much more vulnerable after the film biopic of his life, Love is the Devil. After his death people saw him and his paintings in a very different way. He was openly homosexual at a time when it was still an imprisonable offence; he hid nothing from the world.

I guess you’re doing a similar thing – hiding nothing from the world.

Yeah, my emotions are right at the front of everything I do. It’s a bit old-fashioned. Bacon was also putting it out there, as were Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele. What they did had nothing to do with any art movement, or with what was fashionable. They were working within their own psyches. If you look at Bacon’s work and think about what was fashionable in the 1950s, he was really unfashionable. He was an alcoholic and didn’t give a fuck about anybody – not a combination for success actually.

Well, he did all right. But he didn’t really enjoy his celebrity.

Yeah. I’m sure that when I’m his age, I won’t enjoy mine either.

Are you enjoying it at the moment?

Less and less. I’m sure it will be only a matter of time before I disappear into obscurity.

I doubt that very much, Tracey.

This interview was first published in Tate Etc. (Issue 34, Summer 2015), with which Momus is engaged in a partnership.