I wanted to make “the fourth wall” no longer a mirror, but a membrane that makes the spectator aware of this coming and going of appearances and disappearances that is constructed by the relationships between them, their perception, and the actions of performer.

- Xavier Le Roy to RoseLee Goldberg, Performa Magazine, 2007

“Retrospective” pushed me to think about what I can do in exhibition spaces that I cannot do in theater.

- Xavier Le Roy to Samara Davis, Artforum, 2014

- Xavier Le Roy began dancing and choreographing in 1991. Before then he did things like complete a doctorate in molecular biology. His work interrogates bodies and the relationships that form among them in performance.

- MoMA PS1 presented an exhibition titled “Retrospective” that ran from October 2, 2014 to December 1, 2014. It involved audience members talking with and watching dancers who changed what they did often.

- “Retrospective” pushed us to think about what we can do in a critical space that is like a membrane and not like a mirror. The way dancers could talk to spectators might be like the way critics talk to each other, we thought.

- For clarity: A is not B and 2 comes after 1.

A1.

Ordinariness is defined by repetition. Ordinary things are everyday things that happen “every day” – routines, practices, habits, patterns. “Extraordinary” things, then, are things that happen once or just a few times. They are memorable because they are limited. Having an extraordinary thing happen a lot of times would make it fairly ordinary. But is there a zone in between the ordinary and the extraordinary? A zone between the general and the singular? There are certainly parts of a day one doesn’t remember that are neither perpetual nor occasional: blips, interruptions, and dissonances that don’t follow routine yet are completely forgettable. These moments are noticeable, they stop the progression of the ordinary, but are quickly subsumed into the general fabric of the everyday. For the most part.

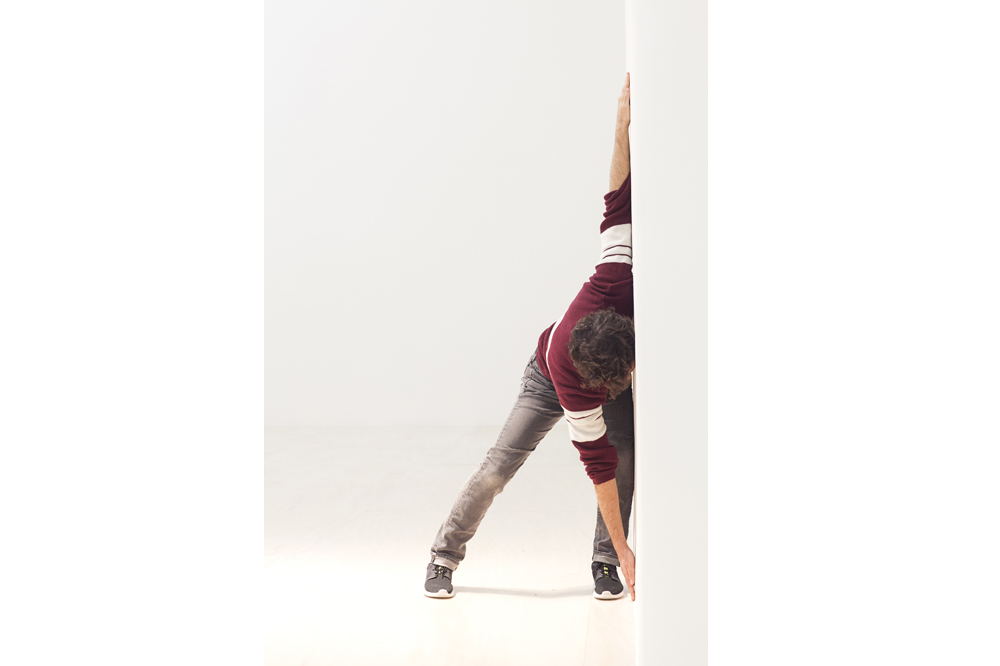

An exhibition at MoMA PS1, Retrospective by the French choreographer Xavier Le Roy, expressed the quality between the ordinary and the extraordinary (the meso-ordinary?) through the medium of dance. The museological set-up was fairly ordinary: one walked into a large white gallery flanked by two narrow, long rooms – staging platforms of sorts. One of them led to another gallery with computers and books about Le Roy.

The majority of the action was in the first room. When the visitor walks in, people in ordinary clothes whistle, mimicking the factory noise that marks the end of a shift, and run around until they surround the visitor. A handful of dancers – the number seems indeterminate – each say a year and begin to execute a fragment from one of Le Roy’s pieces created between 1994 and 2010. The remaining performer, or host, or person, greets whomever walked into the gallery and describes the exhibition, their biography, and/or Le Roy. The performers switch roles at intervals, alternating between chatting and dancing, talking and moving. One person narrated how she was pregnant in the past and had to take a break from dancing; another, who had injured herself, explained the dances happening around her. A third explained her interpretation of a dance titled Xavier makes someRebutoh, from 2009, where the curator Boris Charmatz asked Le Roy to design a butoh dance in only two hours.

The actual dances assume a quality somewhere between minimalism and expression, between the ordinariness of movements that sustain everyday locomotion and the extraordinariness of trained, professional, skilled dancing. They seem like blueprints, schematics for motion writ large: one dancer ran laps; another sat down, held his knees, and faced the wall; another moved through a series of generic pantomimes, as one of the didactic performers explained, like pissing, bowling, and holding a baby. Dressed in street clothes, the performers made their dances seem neither theatrical nor average; rarely flashy and rarely boring.

B1.

There’s a touch of comedic paradox in the idea of a performance retrospective, or of a retrospective performance. In her important 1993 volume Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, scholar Peggy Phelan declares, “Performance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.” Similarly, during a recent symposium addressing Retrospective, curator Laurence Rassel observed the tendency of performance to become a document when placed within a gallery space, and emphasized finding ways to avoid this. Meanwhile, the historicity of the retrospective defines its genre, and its orientation to the past is legible even in the etymology of the term.

Retrospective makes use of the tensions that bisect these disparate constructions, and as a “performative exhibition” it has more in common with how Saint Augustine engages the past in his Confessions, than with the retrospectives typically found in contemporary art institutions. Considered the first example of autobiography, Confessions follows a methodology in which assembling the past is not a process of replication, but one of active creation. For Saint Augustine, constructing his own past functioned as a way to explore the spiritual realities of his current worldview.

Le Roy’s Retrospective does not dawdle in the grand narratives of a choreographic career. Rather it explores the potential for choreographies, and our experiences with them, to reconstitute our engagement with performance in the present. “Retrospective” invites its performers to integrate their own histories with those of the choreographer’s work, and welcomes the audience to enter into this productive encounter.

We feel this temporal dynamic in moment when each dancer states the year their respective piece was first performed, before themselves performing it. Their utterances do not roll off the tongue confidently, with the authority of a printed wall posting or program note. Rather, the performers take their time, they hesitate; sometimes it seems they are still making up their minds as to which section they will perform even as they’re speaking. Such instances illustrate how “Retrospective” actively imbricates the past with the present. Declaiming these years, the dancers do not merely delineate a timeline of past dance-making, but also mark the imminent opportunity for a new, embodied experience of choreography. The work becomes a relational exercise of doing the past now, and in the future. Somehow, Le Roy has negotiated both a presentness for the retrospective, and a futurity.

A2.

Because each interaction, each dance, each performer, and each visitor is different whenever the gallery is open, there is by definition no singular way to approach Retrospective, ironically named because its components are, to some degree, always up for grabs, unlike a standard exhibition. (There is in fact a roster of 16 performers who take shifts through the exhibition’s roughly three-month run). Once you understand this, or once you just ask a dancer how the whole thing works, you can’t figure out which moments are spontaneous and which are planned. In a flash of uncharacteristic dramatics, one dancer was describing the idea of female hysteria to some participatory interlocutors before she screamed as loud as she could with wrenching volume, running from corner to corner at an agonized pace.

Admittedly, Retrospective adapts the cosmopolitan, sensibly fashionable mien of contemporary art, namely the functional and generic availability of relational aesthetics (cross-reference a similar adoption, both stylistically and curatorially, in Tino Sehgal’s 2013 exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal). The walls are white, the performers are sensibly dressed, and museum-goers still adopt the posturing of inquisitive but not intrusive cultural consumers. So moments like that hysteric screeching hint at something darker underneath Le Roy’s experiment. As that same screaming person said later, “We’re specimens here.”

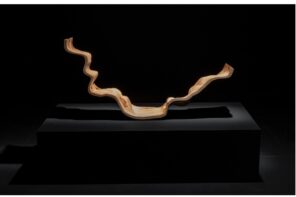

Consider an installation two rooms behind the central action of the main gallery titled Untitled, from 2005. The space was almost pitch black. As your eyes adjusted, you could see slouching figures on the floor, dressed nondescriptly in sweatpants and hoodies. They never moved, but given the performers assembled in the adjacent chambers, you couldn’t be sure as to whether this was live performance or sculptural placement. It didn’t read like a humorous riddle, but rather an unnerving confrontation. Awash in the insecure theatricality of Untitled, any proximate conversation between spectators became over-determined, as if on stage. Chatter about using the bathroom could or could not be scripted. The figures were in fact dummies.

If the life of performance is only in the present, like Peggy Phelan says, then in “Retrospective,” part of that tense is constantly figuring out what registers as performance and what doesn’t, what’s in and out of the ordinary as it’s happening in real time. “Presentness is grace,” goes an old art-historical mantra, but presentness is also awkward and uncanny, and rarely graceful. When you start being present to your ordinary movements and routines, as Le Roy nudges his audience to realize, “embodied choreography” just means how you get through the day with all the clumsiness and agility it implies.

B2.

Repetition relies on sameness while simultaneously revealing difference. Repeat something enough, and you will eventually begin to see the slight variations that emerge. You may even see these variations with only a little repeating. In videos, shown at the symposium, featuring the Quatuor Knust’s reconstruction of Yvonne Rainer’s Continuous Project – Altered Daily in 2011, the repeated gestures – simple displacements of pillows on and around chairs – are striking in the way they fall in and out of unison with the embodied pacing of each performer.

Choreographers around the Judson Church movement in the 1960s and ‘70s, Rainer among them, insisted on the everyday. As dance historian Sally Banes writes, “The found gesture – whether from everyday life or ‘commercial’ dance – was used in dance in much the same way that the found object – either junk or the imagery of commercial art or ordinary industrial products – was used in fine art.” This work actively broke down the hierarchies of movement and bodies in dance, and as Rainer mentioned at the symposium, once you begin the demolition project, it becomes an ethical imperative.

And yet the everyday has problems too. In The Practice of Everyday Life, first published in French in 1980, philosopher Michel de Certeau poetically examines how structures of power strategically map our quotidian movements and experiences.

How do we respond? Perhaps the space between the ordinary and the extraordinary – the meso-ordinary – makes room for our “tactical” interventions. And maybe Le Roy’s Retrospective functions in this register. His movements both enact and transcend the everyday. In one oft-repeated excerpt, the dancer moves like a robot, making sound-effects, too. This is not material from the everyday, per se, and yet it develops with a sense of ordinariness: in the casual tone of a child at play within their own slightly sci-fi version of reality. So maybe we can revise. Maybe Le Roy encourages us to do a little more than “get through the day with all its agility and clumsiness.” The performers, after all, don’t merely move through Le Roy’s choreographies. They actively re-contextualize them. The dancers approach each dance as new interlocutors, like they do with each new spectator who enters. With such a framework, maybe we can act in the meso-ordinary together, to make the process of getting through the day something we experience on our own terms.