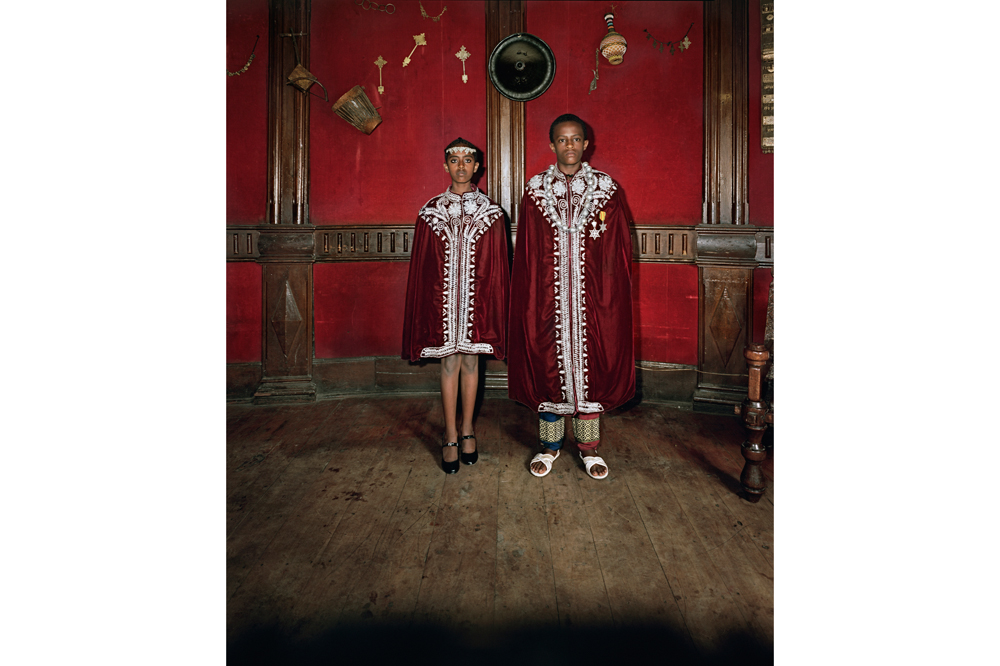

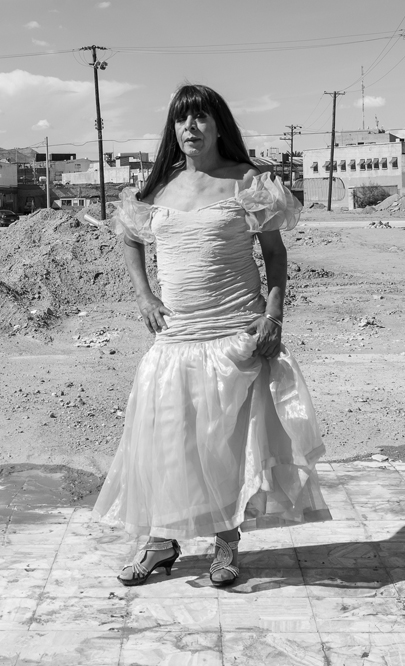

Tented within Manhattan’s industrial piers, and under a cold sweep of wind, the Armory Art Fair rounded out its latest edition (under new director, Benjamin Genocchio) with an increasingly common feature in these commercial circuits: a section shaped by a curatorial hand. In an effort to perhaps soften the reality of art-schilling, or inject some air into the close space and frenetic pace of a five-day fair, this year’s curatorial conceit abandoned the geographic focus of past years, and comprised instead an articulated theme – broad though it was. Curator Jarrett Gregory was at the helm of this year’s Focus section (a name not unlike the fair’s other sections, Insights, Presents, Platform, etc.), and centered on the question, What Is To Be Done? The area, measured out in gallery booths, featured 12 solo-artist presentations including work by Deana Bowen, Teresa Margolles, Anya Titova, and Johan Grimonprez. The projects spanned the spare (Margolles’s paean to a murdered trans sex worker from Mexico, anchored by a larger-than-life portrait, and the rock used to bash her head in) and the chaotic (Koki Tanaka’s messy and didactic Between Man and Matter clashed with everything in its proximity, including a subtle sound piece by Roman Opalka, which it ran right over). By contrast, there was an affecting set of video pieces by Grimonprez that worked unusually well by being presented in a cloistered space, where the dark and quiet of its alcove marked a welcome reprieve from the rush of the fair – a feat of clear delineation that the rest of the Focus section struggled to match.

What is an art fair doing asking “what can be done?” In even the darkest political moment, is this the right space for asking such a question? Or is it exactly the right place for asking such a question? Momus publisher Sky Goodden sat down with curator Jarrett Gregory to parse the potential absurdity of this gesture, and consider the limitations and affordances of curating from within the market’s deep.

Certain things have to be taken into consideration when curating in this kind of environment. You have, very ambitiously, chosen a political theme. What are some of the things you’re up against in a space like this?

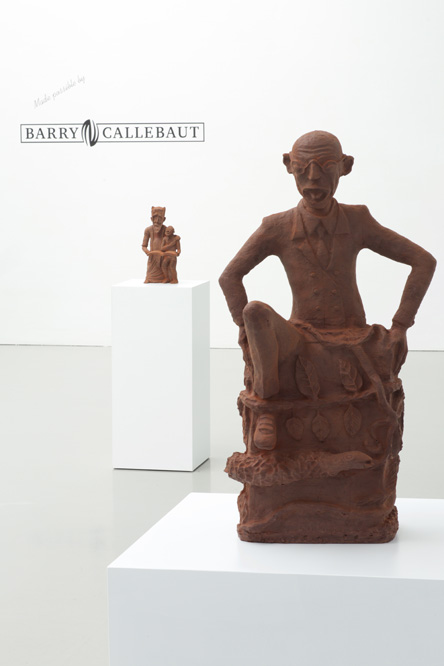

It being an art fair heavily influenced my choices. Curating is always contextual – whether it’s one art fair over another; one city over another. This is a highly charged environment, so I wanted to address the idea of economy, specifically. I wanted to take a different point of view on that; the objects we give incredible value to. I spoke to artist Renzo Martens yesterday, for instance, and he said the chocolate works [made by Cercle d’art des travailleurs de plantations congolaises, founded in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2014] increases by 7,000 % by becoming an art object. And these are fairly modestly priced.

So I think the economy of these things is fascinating, and entwined with politics.

Djonga Bismar & Jérémie Mabiala, “The Art Collector,” 2015. Chocolate. Photo: Ernst van Deursen. Courtesy Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam; and KOW, Berlin.

In your brief curator’s text, you write, “This project emerged from recent trips to Russia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where I witnessed causality on a global scale, including social and economic failure.” To parse some of the language you use, what do you mean by “witness causality”?

I did a lot of traveling in the past six months for research. And when I started off, I felt that I was basically following projects and artists that are interesting to me. What I began to understand, though, was just how interconnected all of these economic systems are with one another. For example the plantation system and how the success of Europe and the West was built on the backs of people working for the plantations for no money, a different form of slavery. Going to Ghana, spending time in Moscow, I saw communism in action in Vietnam … I began to understand a different kind of capitalism, and the desire to break free from it. I mean by “witnessing causality” seeing cause-and-effect on a global scale.

Installation view of Raymond Tallis, “on tickling,” 2017, at Sean Kelly, New York. Photo: Jason Wyche. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York.

There are some binaries you use in the text – “art and reality,” “creation and participation,” among others. Are these not false binaries? You’re putting things at a distance from one another that maybe don’t need to be distinct.

Sure. Well in the sense of art and reality I mention the elastic relationship they have, and I think that in some cases artists make their work distanced from whatever is happening in their world, while other artists are engaged in it. I’ve thought about the word “reality” a lot, because it’s a strange word to use in that context. I like the idea of it as a driving force, as something that art comes close to, and backs away from at different points.

It struck me as interesting because I was just reading an interview with the writer Teju Cole where he was agitating against the distinction that gets made in literature, between fiction and non-fiction. And then he pointed out that when we walk through a museum, for instance, we’re not pointing to a Monet and calling it non-fiction, and at an Ingres painting and calling it fiction. We don’t make these distinctions in art. And here, it seems, you are.

I didn’t mean it that way. The nuances are what interest me. I definitely don’t believe in a fictitious or non-fictitious practice or artwork. But it’s more about the vector of truth that we move towards or away from.

Koki Tanaka, “Provisional Studies: Workshop #1, 1946–52 Occupation Era, and 1970 Between Man and Matter,” 2014. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space.

Galleries are featured prominently in this exhibition. So booths run by galleries feature the artists you’re presenting, one by one. But we wouldn’t see galleries foregrounded in a museum, of course. Does the fact that this section is articulated through galleries hinder your articulation of an idea? How did this reality shape things for you?

I curated this like I would a museum exhibition, because that’s what I know how to do. The major difference being that once I selected the artists I had to approach galleries to get their support. That was another restriction – there were a lot of artists I would have liked to approach that aren’t represented by galleries. So it hasn’t changed anything in terms of how I do things; ultimately it’s still the same gesture, with one added step.

I assume you made these curatorial decisions before the current political moment erupted. Has this selection of artists, or this curatorial framework, taken on a different charge in recent months or weeks?

Its meaning hasn’t [changed] really, but it’s much more relevant for a lot of visitors to this section. But the political angle was not about the current political situation; it was about an enduring situation that has been preoccupying me, that’s much larger. I know there’s a desperation right now, about how bad things have become; but I think it was already bad, is my point.

Are you concerned about a show with this political potency at its center, sitting in this art-fair environment, appearing absurd or impotent?

To be honest, it’s a question I’d prefer to have more time to answer. [Because] I don’t want to defend anything. [Pauses] Let me ask you to clarify, what about this context would make it absurd?

That this is not a place for contemplation. Its existence is one driven by the market. Art does not breathe well in an art-fair environment. People and business, here, move very quickly. I like the sincerity or optimism of what you’re doing, but is this not the wrong environment for it?

I have only worked in museums [but, for me], it’s not the wrong environment, but an exciting one. I’m not trying to get everyone to stay an hour or stop writing cheques. I don’t have any goals, that way. But you’re right that it was done with a lot of sincerity. The gains for me were to work with these artists, work through some ideas; if it achieves some contemplation for even just a few visitors or artists, I’m happy. For the artists to get a little bit of exposure they haven’t had before, I’m happy.

The fair gave me carte blanche, which is why there’s no geographic focus this year, and why it’s thematic. One of the artists the other night, she compared this section to a Trojan horse. I liked that, because in a way it enters into this conversation and does something different with it. I’m not expecting it to change the world, but hoping it might affect some people, I guess.

Yes, though you ask in your text, “what can art do?” And I wonder when we will exhaust that question. Why do we ask art to do something?

I felt the opposite. It’s something we used to ask of art all the time, but with the art market going crazy, and the [emergence of] art stars, and all this, I feel like we’re not asking it enough. I don’t mean art should function, that it has a responsibility. But I’m wondering, if it wants to do something, what is its potential, what can it do? Like the Congo project has been fascinating for me, because it’s an example of a group of artists wanting art to do something. I don’t think every artist in the section has that same goal, but for me, I am intrigued by its potential as a tool.